Abortion care information for health practitioners

The Abortion Legislation Reform Act 2023 (WA) came into effect in Western Australia on 27 March 2024. The new laws aim to address inequity of access in line with other Australian State and jurisdictions and removed clinically unnecessary barriers for women and people accessing an abortion.

For detailed information about the amended laws and health practitioners responsibilities, see the Department of Health website (external site).

For detailed information about referral and management pathways, please refer to Clinicians Assist WA (external site).

Health practitioners should be aware that:

- abortion is a safe procedure

- abortion is legal up to 23+0 weeks gestation in Western Australia,

- abortion is legal after 23+0 weeks gestation in Western Australia in specific circumstances

- there are two options available for abortion: medical and surgical

- routine medical and surgical abortion care can be accessed through community health services (PDF).

Health practitioners should also consider:

- arranging a dating ultrasound scan as soon as possible if there is uncertainty about the date of first day of last normal menstrual period.

- providing an appropriate and supportive environment for assessing the patient to ensure as far as possible that there has been no coercion or pressure on the individual.

Please note that this information refers to pregnant women and people, as it also includes people who are gender diverse and girls.

Requirements for abortion up to 23 weeks

An abortion may be performed at less than 23 weeks using either medication or a surgical procedure. Early medical abortion (up to 63 days gestation) is safe to provide in primary care when provided within scope of practice and training. Early surgical abortion is also available. It is important to ensure that those wanting abortion care are informed that the risk of complications from the procedure, and costs, rise with increasing gestation.

The legislation (external site) outlines the conditions that need to be met to provide abortion care at less than 23 weeks.

It is important to ensure that those wanting abortion care are referred as early as possible, as the risk of complications from the procedure, and costs, rise with increasing gestation.

RANZCOG Clinical Guideline for Abortion Care 2023 (external site)(1) recommends considering the use of an additional specialist medical procedure for abortions beyond 22+0 weeks.

Requirements for abortion after 23 weeks

Medical practitioners can contact the KEMH Pregnancy Choices and Abortion Care clinic for information and advice on requirements for abortion after 23 weeks. Contact details for the Pregnancy Choices and Abortion Care Coordinator can be found on Clinician Assist (external site) or alternatively, call via Switchboard on (08) 6458 2222. The clinic operates between Monday to Friday from 8.30am to 4.30pm.

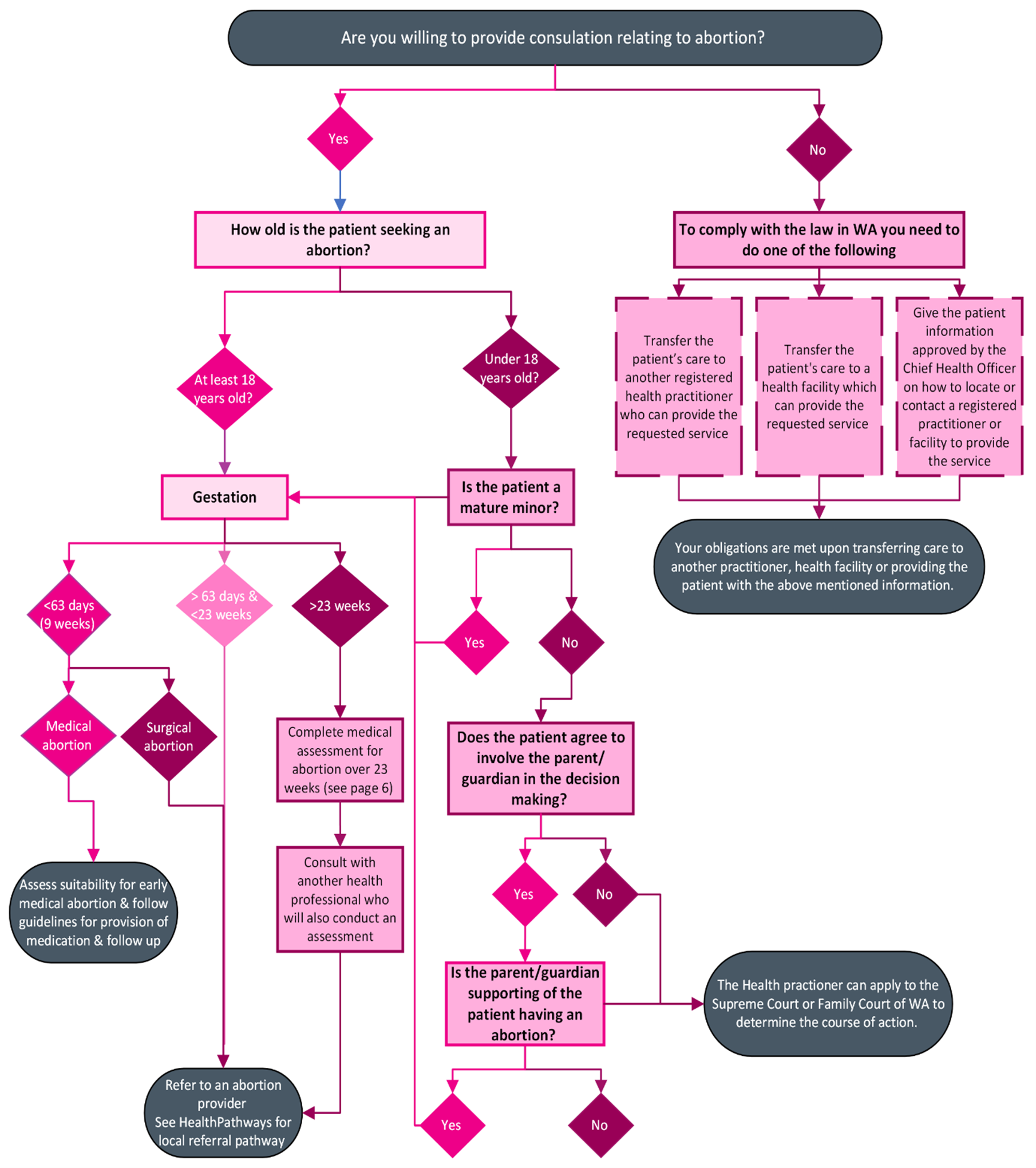

Mature minors and parental involvement

For information on content requirement for an abortion on a person aged less than 18 years, visit the Department of Health website (external site).

If the person is aged 14 years or less, contact the KEMH Pregnancy Choices and Abortion Care clinic for advice. Contact details for the Pregnancy Choices and Abortion Care Coordinator can be found on Clinician Assist or alternatively, call via Switchboard on (08) 6458 2222. The clinic operates between Monday to Friday from 8.30am to 4.30pm.

How is the health practitioner involved in the application process?

If the minor does not wish for parent / legal guardian involvement or the registered health practitioner is of the view that the parent or legal guardian is not acting in the best interests of the child, the registered health practitioner can apply to the Supreme Court or the Family Court of WA to determine the course of action.

Pregnancy following sexual assault

Unwanted pregnancy may be the result of a recent sexual assault. If there is disclosure of a sexual assault, consider the following points:

- Determine accurate gestation. An ultrasound will confirm gestation and allow correlation with alleged date of incident.

- Ask the patient if they would like a referral to sexual assault counselling. This can be done through the Sexual Assault Resource Centre (SARC), Family Services or Sexual Health Quarters.

- Contact SARC duty officer on (08) 6458 1820 if you would like more individualised advice.

- Ask the patient if they would like police involvement. Note that products of conception can be used as DNA evidence and this can be requested by police and taken as evidence.

- It is possible that the patient is at ongoing risk of harm. Follow the Shared Maternity Care (PDF) provider (WA) - Referral Pathway for Family and Domestic Violence (page 12-13) to screen for FDV and complete the appropriate risk assessment.

- For more information, see the Sexual Assault Resource Centre which has information for clients and health professionals.

Under 18 years of age

If the health practitioner has a reasonable belief that a person under 18 years of age has been sexually abused, a mandatory report to the Child Protection Unit is required, even when the patient is considered a mature minor. See Mandatory reporting of child abuse and neglect (external site).

Self-managed abortion with unregulated medication

With the increased availability of abortion medicines via the internet, it is possible health practitioners will see patients who have attempted, or intend to attempt, self-managed abortion without clinical supervision.(2)

It is important that patients are aware of the need for medical supervision and appropriate medications for safe and effective abortion. Some online abortion medications are unregulated and may be counterfeit.(3) Risks include failed treatment, health risks to the patient and risk to subsequent pregnancies.(4) If a patient has used unregulated medication for a self-managed abortion, they should be encouraged to seek medical treatment.

Statutory notifications

The Abortion Legislation Reform Act 2023 has introduced a framework for the collection, use, management and disclosure of abortion information, see the Department of Health factsheet on Statutory notifications requirement changes (PDF).

The information required is statistical in nature only and does not include any identifying particulars of the patient, health practitioner or the circumstances of each abortion.

Notification by health practitioner of induced abortion

Visit the Department of Health website (external site) for information on notification by health practitioner of induced abortion.

Referrals

The below Quick Access Guide Table outlines your obligations as a health practitioner and referral pathways for each gestational limit.

Refer to Clinician Assist and Referral Access Criteria for local and up to date referral pathways and requirements and contact your local Health Service Provider regarding gynaecological services and reproductive health.

Ethical obligations - understanding your obligations

Health practitioners have the right under legislation to have a conscientious objection to abortion and can refuse to perform an abortion, assist in the performance of an abortion, or make a decision as to whether performing an abortion on a person is appropriate. However, under the Public Health Act 2016, a practitioner who refuses to participate in abortion must, without delay, transfer the patient’s care to another registered health practitioner who they reasonably believe can provide the requested service, or refer the patient to a health facility which they reasonably believe can provide the requested service.

These provisions do not alter the duty required of a registered health practitioners to perform, assist with, make a decision about, or advise a patient about a termination of pregnancy in an emergency, where it is their duty to assist.

Health practitioners should be aware of their obligations as outlined in the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency (AHPRA) and Medical Board of Australia’s Good Medical Practice: a code of conduct for doctors in Australia.

The relevant sections of the Good medical practice: a code of conduct for doctors in Australia 2020 (external site) include:

3.4 Your decisions about patients’ access to medical care must be free from bias and discrimination. Good medical practice involves:

3.4.1 Treating your patients with respect at all times.

3.4.2 Not prejudicing your patient’s care because you believe that a patient’s behaviour has contributed to their condition.

3.4.3 Upholding your duty to your patient and not discriminating against your patient on grounds such as race, religion, sex, gender identity, sexual orientation, disability or other grounds, as described in antidiscrimination legislation.

3.4.6 Being aware of your right to not provide or directly participate in treatments to which you conscientiously object, informing your patients and, if relevant, colleagues of your objection, and not using your objection to impede access to treatments that are legal. In some jurisdictions, legislation mandates doctors who do not wish to participate in certain treatments, to refer on the patient.

3.4.7 Not allowing your moral or religious views to deny patients access to medical care, recognising that you are free to decline to personally provide or directly participate in that care.

Abortion information

A pregnancy may be ended using surgical or medical techniques or a combination of both.

Medical abortion

Medical abortion refers to the use of medication to terminate a pregnancy.

In July 2023, the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) approved an application from MS Health to amend restrictions on the prescribing of MS-2 Step (Mifepristone and Misoprostol). MS-2 Step is indicated in females of childbearing age for the medical termination of an intrauterine pregnancy, up to 63 days of gestation.

Previously, MS-2 Step was only able to be prescribed by a medical practitioner (a doctor) who had been certified to prescribe the medicine, and then dispensed by a pharmacist who was a registered dispenser. The TGA’s decision means that MS-2 Step can now be prescribed by any health practitioner with appropriate qualifications and training, without the need for certification. The legislation change also extends prescribing rights to nurse practitioners and endorsed midwives and, restrictions on dispensing that limited access to registered pharmacists have also been lifted. It is recommended however that those providing medical abortion care, undergo training that is available to registered health practitioners.

Medical abortion involves the use of two agents – Mifepristone, a synthetic anti progesterone, and Misoprostol, a prostaglandin analogue. The procedure involves oral Mifepristone which inhibits the action of progesterone in maintaining the pregnancy and therefore cause the embryo and placental sac to separate from the wall of the uterus.

Misoprostol, taken 24 to 48 hours after Mifepristone, induces contractions, cervical opening and causes the evacuation of contents of the uterus.

The combination of Mifepristone and Misoprostol for patients in early pregnancy results in complete abortion in 95 per cent of cases.(6) The other five per cent of patients may need surgical evacuation for retained products of conception.(5)

Medical abortion can be offered in a primary care setting or through a clinic. After nine weeks gestation medical abortion is not available in the community but may be available as a hospital inpatient.(5)

Patients undergoing medical abortion will have medical supervision and access to surgical treatment if required. Having a further procedure may incur an additional cost.

Surgical abortion

Surgical methods include suction curettage (vacuum aspiration) or dilation and evacuation (D&E). Aspiration techniques can generally be used up to 12 to 14 weeks; however, as gestation increases, safe removal may require cervical preparation and a combination of techniques to remove the products of conception from the uterus.(7) Surgical abortion is available in licensed day surgery clinics and in hospitals.

Availability of medical and surgical abortion

- Suitability for medical or surgical abortion requires consideration of a range of factors including gestation, the patient’s individual circumstances (for example: psychological impacts, social support); medical conditions; and the choice of abortion provider. All evidence indicates that both medical and surgical abortion are safe. The specific type of abortion provided (medical or surgical) will be determined by an individualised assessment.

- RANZCOG Abortion Decision Aid tool (PDF) was designed to guide discussions about the decision between a medical or surgical abortion and can be used when discussing abortion options with a patient.

- Early medical abortion is a service safe to offer in general practice up to 63 days gestation (noting that after 70 days as per RANZCOG guidelines (external site)(1) patients should be admitted to hospital for medical abortion) There are guidelines and training available to guide the establishment of an early medical abortion service with community based general practice and primary care settings. Many GPs already provide this service.

- Routine abortion is generally provided through private abortion clinics in the community. The provider may offer early medical abortion as an outpatient or a choice of medical or surgical abortion at a clinic.(8)

- KEMH does not provide a routine abortion service; however, it does have an abortion service to assist patients who are unsuitable for private abortion clinics due to:

- medical co-morbidities

- anaesthetic issues

- a fetal abnormality identified in this pregnancy

- social circumstances that exclude them from community-based abortion providers

- being aged 14 years or less.

- Any young woman or person under 14 years of age requesting an abortion should be referred to KEMH. This is a specialised service available to all young people under 14 years from across WA.

- Patients with restricted financial circumstances that would preclude them from accessing private abortion providers may also be referred to KEMH for assistance. This will involve a consultation conducted via telephone between the Pregnancy Choices and Abortion Care Co-Ordinator and the person via a referral from their GP.

Risks of induced abortion

All of the available evidence indicates that induced abortion both via medical or surgical methods, especially in early pregnancy, is a low-risk procedure.(7) The risks of death and serious complication with induced abortion are lower than the risks of carrying a pregnancy to term.(9, 10) Please refer to the RANZCOG Clinical Guideline for Abortion Care 2023 (PDF)(1) for all risks and complications of induced abortion and carrying a pregnancy to term.

Contraception

A request for abortion is an opportunity for clinicians to discuss a patient’s future fertility intentions and use of effective contraception after abortion. It is important that patients are provided with information and counselling to help them make informed choices on suitable contraceptive methods after abortion.(11) FSRH Clinical Guideline: Contraception After Pregnancy (external site) (Chapter 3: Contraception after Abortion)

Effective reliable contraception reduces the rate of unintended pregnancy, and consideration of long-acting reversible methods is recommended by professional guidelines:

- RANZCOG - Clinical Guideline for Abortion Care 2023 (PDF)

- FSRH UK - Clinical Guideline: Combined Hormonal Contraception (external site)

- RCOG UK - Best Practice in abortion care paper (external site)

Contraception can be initiated at the time of early medical abortion or follow-up or provided at the time of surgical abortion. If there is a delay in provision of the chosen contraceptive method, a temporary / bridging method of contraception could be considered.

See below links for additional information and resources on contraception after abortion.

- Contraception after an abortion (external site)

- RANZCOG Clinical Guideline for Abortion Care (PDF)

- RANZCOG Abortion Decision Aid tool (PDF)

- The Complete Multilingual Guide to Contraception in Australia (external site)

Reproductive coercion

Family, domestic and sexual violence is the use of a range of tactics by an abuser to create vulnerabilities, and to achieve power over a partner through coercive control. This includes physical violence or other forms of violence including emotional and psychological abuse.

Reproductive coercion is behaviour that interferes with the autonomy of a person to make decisions about their reproductive health. It includes any behaviour that has the intention of controlling or constraining another person’s reproductive health decision-making, for example:

- controlling or sabotage of another person’s contraception.

- pressuring another person into pregnancy

- controlling the outcome of another person’s pregnancy, e.g., forcing someone towards abortion, adoption, care, kinship care or parenting.

- forcing or coercing a person into sterilisation, including tubal ligation, vasectomy and hysterectomy.

Health professionals can assist by being aware that people seeking an abortion might have been exposed to reproductive coercion or family, domestic or sexual violence.(12) If suspected or disclosed, please refer the patient on to an appropriate service which could be the Women’s Domestic Violence Helpline, a Women’s Health Centre (list of contacts to nearest centre available at the bottom of this webpage, see Resources), or a Family and Domestic Violence Hub (external site). The service will be able to support the individual with a risk assessment and provide further supports as required.

See KEMH Women’s Health Strategy and Programs Family and Domestic Violence Toolbox for more information on intimate partner violence and resources.

Information on coercion and the appropriate support and referral pathways is also available on Clinician Assist WA (external site).

Sexual Health Quarters Safe to Tell (external site) has a number of resources, e-learning for clinicians and contact and referral information for patients experiencing reproductive coercion and/or intimate partner violence.

The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners has clinical resources and training on identifying and responding to intimate partner violence RACGP - Intimate partner abuse and violence: Identification and initial response (external site)

Additional training and resources for reproductive coercion and intimate partner violence include:

- Reproductive abuse | 1800RESPECT (external site)

- Domestic and Family Violence Response Training (external site)

Adoption

Information on adoption is provided as some people may wish to consider adoption or kinship care as an alternative to parenting or abortion.

Adoption practices are shaped by society, culture, religion, politics and economics and have changed over time. Adoption has significantly declined in Australia for a variety of reasons, including increased support for single parent families, the emergence of family planning and legislative changes which provide alternative legal options. There were 310 adoptions in Australia in 2018-19; 57 were adoptions from overseas and 253 were adoptions within Australia. Of these, 211 were known child adoptions (ie; adopted by a step-parent, relative or carer) and 42 were local adoptions. There has also been a significant shift away from the secrecy that was associated with adoption to a transparent system which focuses on the needs of the child.(13)

Since 1995, all adoptions in Western Australia have occurred within a policy of ‘openness’ where the birth mother is involved in each aspect of the adoption. Current research indicates that continued contact increases the birth mother’s satisfaction with the process.(14)

The Turnaway Study, a five-year longitudinal study of 956 women and pregnant people seeking abortion care in the United States of America, including 231 pregnant people denied abortion due to gestational limit, found that amongst pregnant people seeking abortion, adoption is infrequently chosen.(15)

It has been suggested that pregnant people tend to choose adoption when there are fewer options available.(15) Patients should be advised that abortion, parenting, exploration of kin support and adoption are all potential options.(14)

For more information on adoption see the Department of Community Development - Pregnant and considering adoption for your child? (external site)

Non-directive pregnancy counselling

Non-directive counselling is a form of counselling that recognises in many situations, people can resolve their own problems without being provided a solution by a counsellor. The service involves a safe and confidential process that allows the patient to explore concerns they have about the pregnancy and the counsellor to provide unbiased, evidence-based information about all options and services available to the patient, where requested.

Medical practitioners and eligible psychologists, social workers and mental health nurses are able to complete non-directive pregnancy counselling training, which will enable them to provide the service and access Medicare benefits for non-directive pregnancy support counselling services. Refer to the current Medicare Benefit schedule, and Royal Australian College of General Practitioners non-directive pregnancy counselling training for further details.

Women’s Health Services

Desert Blue Connect (Geraldton)

Tel: (08) 9964 2742

www.desertblueconnect.org.au

Fremantle Women’s Health Centre

Tel: (08) 9431 0500

www.fwhc.org.au

Ishar Multicultural Women’s Health Services (Mirrabooka)

Tel: (08) 9345 5335

www.ishar.org.au

South Coastal Women’s Health Services (Rockingham)

Tel: (08) 9550 0900

www.southcoastal.org.au

Women’s Health and Family Services (Northbridge and Joondalup)

Tel: (08) 6330 5400

Free call 1800 998 5400 (free call outside of Perth metro area)

www.whfs.org.au

Women’s Health and Wellbeing Services (Gosnells)

Tel: (08) 9490 2258

www.whfs.org.au

Bunbury

South West Women’s Health and Information Centre

Tel: (08) 9791 3350

Free call 1800 673 350

www.swwhic.com.au

Kalgoorlie

Goldfields Women’s Health Care Centre (Kalgoorlie)

Tel: (08) 9021 8266

www.gwhcc.org.au

Port Hedland

Hedland Well Women’s Centre

Tel: (08) 9140 1124

www.wellwomens.com.au

Tom Price

Nintirri Centre (Tom Price)

Tel: (08) 9189 1556

0456 802 061

www.nintirri.org.au

Mental Health Services

Beyond Blue

Tel: 1300 224 636

www.beyondblue.org.au

Lifeline

Tel: 13 11 14

www.lifeline.org.au

Diverse sexualities and genders

Another Closet

www.anothercloset.com.au

Living Proud

www.livingproud.org.au/about

Qlife

Free call 1800 184 527

www.qlife.org.au/get-help

Sexual Health Quarters (SHQ)

70 Roe Street

Northbridge WA 6003

Tel: (08) 9227 6177

www.shq.org.au

Other resources

Adoption Services

5 Newman Court

Fremantle WA 6160

Tel: (08) 9286 5200 or free call 1800 182 178

Ask to speak to the local adoptions duty officer.

www.wa.gov.au/organisation/department-of-communities/pregnant-and-considering-adoption-your-child

King Edward Memorial Hospital

See referring a patient for abortion care at KEMH

Sexual Assault Resource Centre (SARC)

Crisis counselling over the phone from 8.30am to 11pm any day of the week.

You can also request a counselling appointment.

Tel: (08) 6458 1828 or free call 1800 199 888

Women’s Domestic Violence Helpline

Support and counselling for women experiencing family and domestic violence, including referrals to women’s refuges.

Tel: (08) 9223 1188 or free call 1800 007 339

Resources for health practitioners

The Australian Contraception and Abortion Primary Care Practitioner Support Network

AusCAPPS | Medcast

Better Health Channel

Contraception after an abortion - Better Health Channel

Centre for Culture, Ethnicity and Health

The Complete Multilingual Guide to Contraception in Australia - Centre for Culture, Ethnicity and Health

The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists

The Royal Women’s Hospital

- Resources and support are available for providers of early medical abortion

- Early medical abortion procedure summary (PDF)

- Principles of post early medical abortion care (PDF)

- Principles of early medical abortion care (PDF)

- Information for people who have had an early medical abortion (PDF)

- Unplanned pregnancy in violent and abusive relationships

References

- Clinical Guideline for Abortion Care: An evidenced-based guideline on abortion care in Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand (2023). RANZCOG, Melbourne, Australia.

- Moseson H, Herold S, Filippa S, Barr-Walker J, Baum SE, Gerdts C. Self-managed abortion: a systematic scoping review. Best Practice and Research Clinical Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2020;63:87-110.

- Lee JH, Park HN, Kim NS, Park H-J, Park S, Shin D, et al. Detection of Illegal Abortion-Induced Drugs Using Rapid and Simultaneous Method for the Determination of Abortion-Induced Compounds by LC–MS/MS. Chromatographia. 2019;82(9):1365-71.

- Harris LH, Grossman D. Complications of unsafe and self-managed abortion. New England Journal of Medicine. 2020;382(11):1029-40.

- Gynaecologists TRAaNZCoOa. The use of Mifepristone for medical abortion. 2019.

- Goldstone P, Walker C, Hawtin K. Efficacy and safety of Mifepristone–buccal Misoprostol for early medical abortion in an Australian clinical setting. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2017;57(3):366-71.

- Kapp N, Lohr PA. Modern methods to induce abortion: Safety, efficacy and choice. Best Practice and Research Clinical Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2020;63:37-44.

- Mazza D, Burton G, Wilson S, Boulton E, Fairweather J, Black KI. Medical abortion. Australian Journal of General Practice. 2020;49(6):324.

- Gerdts C, Dobkin L, Foster DG, Schwarz EB. Side effects, physical health consequences, and mortality associated with abortion and birth after an unwanted pregnancy. Women’s Health Issues. 2016;26(1):55-9.

- Raymond EG, Grimes DA. The comparative safety of legal induced abortion and childbirth in the United States. Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2012;119(2):215-9.

- Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare. Contraception after pregnancy. Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare. 2017,

- Horvath S, Schreiber CA. Unintended pregnancy, induced abortion, and mental health. Current psychiatry reports. 2017;19(11):77.

- Welfare AIoHa. Adoptions Australia 2018-19. 2019.

- 55 Madden EE, Ryan S, Aguiniga DM, Killian M, Romanchik B. The relationship between time and birth mother satisfaction with relinquishment. Families in Society. 2018;99(2):170-83.

- Sisson G, Ralph L, Gould H, Foster DG. Adoption decision making among women seeking abortion. Women’s Health Issues. 2017;27(2):136-44.